Recently I’ve had the desire to create something physical. Since photography is currently my main passion, some form of printed work was a natural solution. I’ve had a few large prints made, which were momentarily satisfying, but tended to end up in the closet with very little exposure. A book seemed like a better way of satisfying the need for a tangible result that was also shareable. However, after a bit of initial planning, it became apparent that I did not have any projects that were complete enough. Also a book seems like a rather final statement on its subject, and I wanted to avoid the corresponding pressure when selecting photos to include. I’m indecisive enough as it is. The relatively relaxed magazine format seemed like a good compromise. It offered the possibility of future volumes on the same topics, or multiple topics per issue when there was not enough content.

The following covers my experiences creating my first (self) publication.

The Content

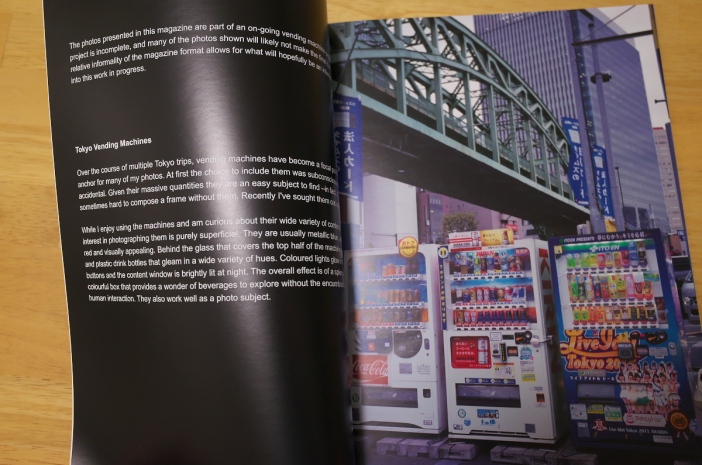

Since I’ve had the creation of a vending machine book in mind for a while, a magazine on that topic seemed like a natural place to start. While the photos I have are not as varied as I would have liked, there are enough of them.

The main problem was the text, which really was a problem of defining what the magazine was about. Although this was an issue featuring Japanese vending machine photos, was it really about the machines, or was it about the photos of the machines. I’m still not entirely sure which is the case and, embracing my perception of the looseness allowed in the magazine format, I ended up doing a bit of both, but not really much of either. The text ended up being along the lines of online photo gallery descriptions, and generally secondary. Often the words were simply driven by a need to visually vary the layout.

The Printer

I did not put a huge amount of effort into determining how to get the magazine printed. Getting bogged down in such matters for my first attempt at a publication might have caused it to never happen. I wanted to concentrate on the content but not so much on the final production and so I went straight to researching companies that would do it all for me. Decent quality and economic print runs at low volume were the main criteria.

The top Google searches pointed towards Blurb, an online on demand printer that could deliver full colour bound books in a variety of formats. I intended to distribute the copies myself but they also offered a marketplace for selling books printed through them, which was a nice option to have. There are several other companies with similar offerings but I really didn’t spend much time researching them. Blurb seemed to be the most reviewed for photo books with reasonable ratings for quality. The prices for their magazine format was okay. Initially the prices seemed great, but shipping is expensive. Apparently shipping costs vary depending on the country and how far away the printer is. Be sure to price shipping before committing to blurb.

The Layout

Another attraction for Blurb is that they offer their own layout software. They also have templates for Adobe Indesign, which I don’t have. The software is really basic. My first reaction was disappointment. I missed such simple elements as coloured text backgrounds and transparency. But upon reflection I decided to embrace the simplicity and was happy to limit my options. The combinations are still practically infinite, and not having design experience it’s probably best that I had fewer tools with which to complicate the layout.

I’m not sure if it was a limitation of the software or Blurb’s magazine format, but I could not find a way to print on the spine. Even with my thin, 36 page magazine, I would have liked to have at least printed a small issue number.

I really didn’t know where to begin and so started with the cover. I figured it was probably wise to put a disproportionate amount of effort into this and worked through a few versions.

For the interior I simply started throwing photos onto pages in varied layouts and then added bits of text that occurred to me at the time, mostly to fill space and balance layouts. Besides adding a bit of interest, the text might also provide some pacing, slowing people down so they don’t breeze through the photos to quickly.

The Result

Before placing the final order I had a single proof copy printed. At $12 Canadian, the cost of shipping a single magazine was a bit ridiculous, but the package arrived promptly and was well protected. The magazine was 36 pages plus cover and cost $10 to print, so the total price of the proof copy, including taxes was just over $23.

The results were better than expected. Layout wise, everything matched what I had seen on screen. I’d heard horror stories about gross misalignments. I suspect such cases occurred when neither Blurb’s software nor InDesign templates were used. Colour and brightness wise the results were good. Only the cover hue was slightly shifted, which was made obvious by the cover’s image being replicated inside where it was better.

The length also made for a decent enough heft. I’d worried it would be too thin, but it felt reasonably substantial.

After reviewing the proof, I corrected a couple of typos and left the cover as is. The cover still looked good and it did not seem worth trying to counteract the hue shift since that would have involved at least one more proof copy.

I decided on an order of 20 copies, which gave me a 20% per issue price break. Thankfully the shipping cost per copy also came down substantially. In the end, including shipping and taxes, each issue cost $12.

The order arrived without fuss. Twenty copies, all individually sealed, in a well packed box. The interior looked identical to the proof, but the cover’s hue was off more than the first copy, although it is hardly noticeable and doesn’t bother me. Overall I’m happy with the result and eager to share the final product.

Conclusion

At this point I definitely intend to create another issue although I may do things a bit differently. I probably won’t alter the technical aspects of the production –sticking with blurb and their software– and continue to concentrate on the content. I feel more significant text would be an improvement. To that end I may consider using articles from this blog, perhaps remixing or extending them.

The process of creating the magazine was highly enjoyable. It also satisfied my desire for a balance between the finality of a book and ethereality of online photo galleries. Even if the process had not been enjoyable, having something tangible to hold in my hand and share with friends, family and fellow enthusiasts more than justified the effort.

I highly recommend that others try producing a photobook, or at least make some individual prints. Making photos a part of something larger than themselves gives them an extra layer of purpose and the scrutiny involved in the selection process can give new insights into one’s work. At the very least, the production of a physical object seems to satisfy a basic need that is all too starved in this world of virtual products.

Konica Pearl 2

Konica Pearl 2